The role of entrepreneurship is to foster social change, in addition to economic growth, and enhance the quality of life for all.

The theme of entrepreneurship is multi-faceted and nuanced, especially in India, where almost 80% of people are self-employed or work in the informal sector. As with most realities of our country, this is paradoxical when we juxtapose the 58 Unicorns — all created 2011 onwards, with almost 64 million micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), most of which are struggling to survive, in the context of severe disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst it is hard to estimate the employment generated by these Unicorns, a key dimension of economic and social progress, we can assume that 64 million MSME families are either partially or solely dependent on their micro or small enterprises for livelihood — that covers a population of approximately 320 million. Conceptually, the 64 million MSMEs fit the definition of “entrepreneurs” (taking financial risk, setting up business, providing employment, etc.), but do not have the resources to scale, or even become profitable enough to have a corpus of savings that they can rely on, in difficult times.

In the 74 years since Independence, India has become the sixth largest economy as measured by GDP; it has 5,000 stocks listed on the BSE and a stock market valued at approximately $3 trillion in July 2021, which grew at 14.7% over the last five years, compared with 13.3% global growth in market capitalisation. Of the top 10 companies in India – (five banks and two IT companies), five were founded in the mid-1980s onwards. No surprise then that the contribution of the services sector to India’s Real GDP has increased from 26% and 37% in 1951 and 1991, respectively, to 54% in 2021. Additionally, most of the 58 Unicorns, of which 40 happened during 2019-21, comprise sectors such as e-commerce, payment systems, fintech, education, social messaging etc. Private equity-venture capital (PE-VC) investments in 2020 were approximately $39 billion across 814 deals and in the first half of 2021 have already crossed $27 billion. This combination of abundant liquidity and speculative fervour has also twisted valuations rather notably.

India’s entrepreneurial footprint in manufacturing, on the other hand, has been lacklustre, constraining integration into global supply chains. Despite the recent pronouncements of ‘Ease of Doing Business’ and ‘Make in India’, etc., the contribution of manufacturing to GDP continues to be rather timorous — from 15% in 1991 to 17% in 2021. In fact, the shift occurred during 1951-81 when the contribution of manufacturing increased from 8.6% to 14% of GDP. It is important to note that no major country has achieved economic progress, without a vibrant manufacturing sector with its capacity and capability to scale, to increase productivity, and to offer large-scale employment. MSME is the second largest employer after agriculture and despite contributing 45% of manufacturing output, has largely remained outside the purview of policy-makers, even after the re-launch of the Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency Ltd. (MUDRA) scheme in April 2015.

It is important to recognise that the role of entrepreneurship — apart from creating and scaling profitable businesses — is also to foster social change and enhance the quality of how people live on a daily basis. This can only be done by effectively addressing the big challenges that transform societies, transform countries and transform our planet. In many ways, the dairy co-operative movement under the visionary leadership of Dr. Verghese Kurien, industrialised dairy (currently 150 million small dairy farmers and small-scale vendors), created one of India’s most iconic brands (Amul), and made India the largest milk producer in the world – though at low levels of productivity, which is an upside opportunity going forward. The model demonstrated that decentralised procurement, which involved tens of millions of small households, could be combined with state-of-the-art production facilities to make milk and dairy products more available, accessible and affordable. At yet another level, Jamsetji Tata confirmed that a business of steel and a heart of compassion could create empathetic leadership, putting social and societal concerns at the centre of governance. As he said, “In a free enterprise, the community is not just another stakeholder in business, but, is in fact, the very purpose of its existence”.

The empirical evidence we now have of the devastating consequences of climate change, makes the most compelling case for societal and environmental considerations to be integral to entrepreneurship and the business model it creates. Unless policy makers, entrepreneurs and companies take that seriously, there is little hope that critical issues such as climate change, access to good quality and affordable health care and education, and improved standards of living for all, will get addressed in a fair and equitable manner.

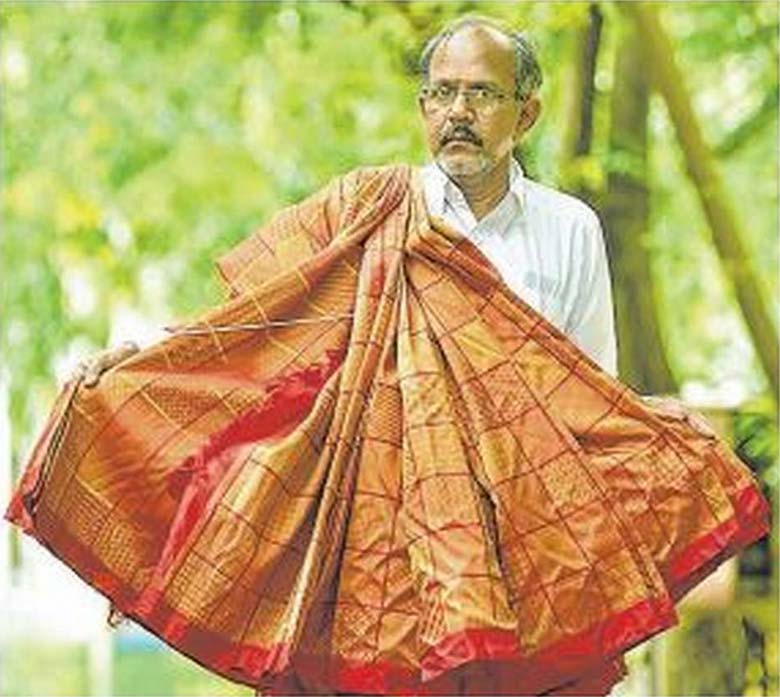

The way forward for entrepreneurship, given the diversity of India, is to work towards an inclusionary ecosystem that prioritises the generation of real value and real jobs, and includes the millions of MSMEs struggling for access to resources and to markets, for they constitute, not just manufacturing units but also artisans, weavers and craftspeople who uphold the critical heritage of India. Our economy cannot be polarised into a productive and globally competitive formal sector, employing 10%-15% of people and a low-productivity “other” sector, including agriculture and micro and small-scale enterprises, employing the remaining 85%. This is a historic opportunity to accelerate development and comprehensively reduce inequality, with relevant and growth-oriented reforms that energise innovative and entrepreneurial endeavour.