Vinita Bali pulled the rug out from under her feet and swept the floor clean, “quite literally”, she laughs. I am visiting the offices of the managing director of Britannia Industries Ltd, one of India’s most popular consumer brands, on what was once one of India’s most iconic campuses, built on a 5-acre property near Bangalore’s old airport.

The Britannia campus shows how much Indian industry itself has changed in 20 years. When it was built in 1989, this campus was heralded for its lavish scale and generous amenities. But the key difference between then and now is in the treatment of real estate: Scale in Britannia has been used to create luxurious transition spaces and denote hierarchies. So the corporate suite is literally “corridors of power”: large closed cabins, executive dining room, limited common meeting areas.

Newer campuses would be much more collaborative.

Bali’s private suite of offices (with a space for Bali, her executive assistant, her secretary, and a waiting area) was inherited; the then managing director had been allocated a large suite in the main office block. Bali joined Britannia in January 2005, at a tumultuous inflexion point for this nearly century-old business. Today, she is credited with its financial and market transformation.

Her first reaction to her office space was to remove the carpet and install a wood-like flooring because she says she wanted to refresh the look and feel of the cabin. The flooring change, then, is perhaps an apt visual metaphor for the management changes Bali went on to initiate in the business.

A study in contrasts

Bali’s workspace is notable for three sets of contrasts. First, it is a combination of old and new interior elements. Bali chose to retain some aspects of the room’s luxuriousness, such as its finely crafted teak-wood presidential desk and six-seater meeting table, and two impressive paintings by Jehangir Sabavala and B. Prabha. She replaced its “imposing” chairs with some “more comfortable chairs”, she says, and added a few potted plants.

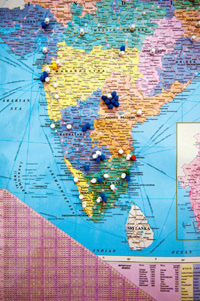

Second, it displays its occupant’s aptitude for operating at different levels: the global and the local, the abstract and the concrete. A photograph of Bali shows her next to former US president Bill Clinton at the Clinton Global Initiative Annual Meeting 2009, speaking about Britannia’s attempts to help tackle major challenges such as malnutrition in India. Just above it is a large map of India, colour-coded to show the individual locations of Britannia’s manufacturing facilities, distribution hubs and sales operations: a detailed overview of the company’s ground-level activities.

Third, the room is indicative of Bali’s ability to think both analytically and creatively. It has the usual signs of business life—two long rows of management books, a laptop with its docking station and a BlackBerry cellphone (“I’m a hard-core BlackBerry user,” she admits). It also has more intellectual fare: books on art, culture and even a stout dictionary (“I love the English language”). A black and white photograph, taken by a former colleague, has been cleverly inserted between two windows to highlight the “play of light”, she describes.

The eclectic collection of books and art reflects her cerebral dexterity. Bali clearly applies both left- and right-brained thinking at work; she is as comfortable advocating the importance of empathy, aesthetics and design in the biscuit business, as she is explaining the granular detail of Britannia’s latest financial results to a stock market analyst.

Multidimensional workstyle

These contrasts serve as analogies for Bali’s layered approach to work. On joining the company, she was keen to retain “all the goodness of Britannia, whether it was good people, products or processes”, yet “wanted to add to it” without compromising either on its lineage or future innovation—arguably her biggest contribution to the business to date.

Bali’s facility to arrive at abstract conclusions, without losing focus on details, is also interesting. My interviews with chief executives have led me to infer this is a defining trait of top management, as the role demands the ability to simultaneously dwell on both big-picture strategy and the minute details of operations.

Bali does not disappoint, offering a compelling insight into Indian managers which highlights her ability to extract abstract conclusions from operating data: “I think in India somehow we underestimate complexity and we overestimate competence, with the result that we’re scrambling.”

Lack of attention to process and project management, i.e. underestimating what it takes to actually accomplish a task, is possibly the result of operating in an “unpredictable environment”, she suggests, as process-driven companies are more effective in predictable environments. While she admits to losing her cool over poor planning and detailing, she realizes that flexibility and pragmatism are important, especially since she’s worked and lived in “six different cultures on five continents” for multinational firms such as The Coca-Cola Co. One must know “when you have to adapt, when to adopt, and when to insist”.

Bali feels her thinking evolved “organically”, rather than through any deliberate effort, and does not perceive any dichotomy between the two modes of thought. As a child, she says she was exposed to the arts as well as sports, and went on to study economics and business management at university. “When you’re dealing with consumers, you’re not dealing with left or right brain, you’re dealing with left and right,” she points out, suggesting that one should approach consumers holistically, and not simply apply either the analytical “left-brain” or more intuitive, creative “right-brain” techniques. Perhaps an obvious observation, but still fairly uncommon among senior management.