How Vinita Bali stemmed a leadership exodus and focused on building strong brands for Britannia Industries after joining the company in 2005

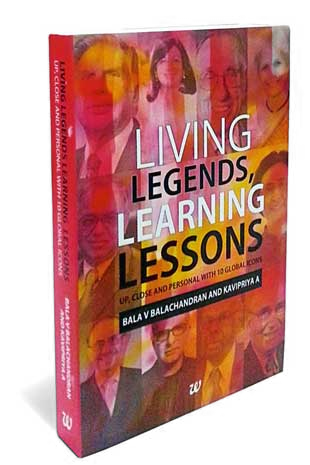

In their book Living Legends, Learning Lessons: Up, Close And Personal With 10 Global Icons, Bala V. Balachandran and Kavipriya A. track the stories of business men and women like Ratan Tata, N.R. Narayana Murthy and Vinita Bali.

Balachandran is professor emeritus of accounting and information management at the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, US, and founder-dean and chairman of the Great Lakes Institute of Management, Chennai. Kavipriya is the founder and chairperson of Adding Smiles Media Pvt. Ltd, which designs branding campaigns and corporate social responsibility strategies.

In a section on Bali, they talk about how she convinced a chocolate maker to shift focus to sugar-based confectioneries in Nigeria and turned around biscuit maker Britannia’s fortunes in India. Bali is said to have scripted the turnaround story of Britannia Industries Ltd when she took over as chief executive officer in 2005, going on to become managing director from 2006-14. Bali stepped down from the post last year. Edited excerpts:

There was no BULB (Britannia Universal Leadership Behaviours) that Vinita demonstrated more abundantly than the drive to get results. This was evident in the manner in which she scripted Britannia’s turnaround story, which warms the cockles of even battle-hardened corporate czars. When Vinita took over Britannia in 2005, nothing was right about the way it was functioning. The nineties had been a period of boom for the biscuit major, led by former head honcho Sunil Alagh’s growth-driven strategy. The early 2000s turned into a nightmare for (Nusli) Wadia as the “crown jewel in his business empire” began to flounder under conflicting visions, internal dissent, and misplaced hubris. As senior leaders began exiting the company under taxing circumstances, Britannia began losing ground to its rivals in the market, precipitating further erosion of managerial talent. The biscuit company was well and truly against the wall when Vinita decided to throw her hat into the ring.

At first glance, Vinita’s legacy and prior experience appeared to be against her. Her experience had predominantly revolved around marketing chocolates initially and then aerated beverages—both a far cry from the world of nutritional biscuits. The marketing philosophy for the latter could easily embrace the notion of “healthy eating”, whereas the same could not be said of the former two products. Also, Vinita had spent her entire career away from India and hence had no first-hand pulse of the Indian market and consumer preferences. And, India was known to be a tough market for the sheer diversity of consumer preferences owing to the spectrum of lifestyles in play and the famed price-sensitivity of the Indian consumer. Lastly, she was attuned to global work cultures which were significantly removed from those that were in play in Indian companies at the time.

Though the problems were aplenty, Vinita did not flinch. Her first hurdle was the void in managerial talent at the top. She wasted no time in drafting in her A-team and establishing an environment that invigorated sagging morale. She also prioritized building on the brands Britannia owned by resorting to aggressive marketing and underlining the “healthy eating” positioning. This was astute reading of the market. Indian consumers had shown a marked shift in eating preferences by the mid-2000s and had gravitated towards healthier lifestyle choices, propelled in no small measure by a global trend of prioritization of health. She began working on creating more “power brands” for Britannia—brands that could be standalone pull factors for the Indian consumer.

In parallel, Vinita began focusing on the inorganic play at Britannia by initiating a series of stake buybacks. First off was Fonterra’s forty-nine per cent stake in a dairy joint-venture. The Fonterra Cooperative Group was a New Zealand-based coalition of farmers who had been looking to multiply their supply channels through the venture. Next in line was the buyout of its high-end bakery retailer Daily Bread in which Britannia had taken a fifty per cent stake in 2006. These stake buyouts were preceded by the wresting of full control of the Rs.3,500 crore Britannia from its foreign partner Groupe Danone, albeit after a lengthy and draining boardroom battle.

The numbers told the story. Britannia’s revenues doubled every four years in the eight-year period between 2005 and 2013, at a Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of twenty per cent. The constantly depleting market-share reversed its trajectory and stabilized at around thirty-five per cent.

Most importantly, Vinita had arrested the exodus of leadership and installed a new team brimming with business confidence. Not only was Wadia’s biscuit empire safe, but its newfound aroma also had started wafting in the corridors of corporate India.

Vinita perhaps drew from her own previous experience with Cadbury in Nigeria. In the eighties, Cadbury had conceded significant ground to competitors in the Nigerian market. It anointed Vinita to turn things around, who advised the company to exit its chocolates business and focus solely on its sugar confectionery business. Though this ran counter to prevalent thinking, it worked. Inexplicably, Cadbury turned itself around, and emerged with a stronger market-share and consumer base. Explains Vinita, “The Nigerian stint taught me how sometimes quick decisions need to be taken and one has to rely on gut too and not just on numbers.” This also hinted at another legendary trait of the Britannia head honcho—that of readiness to test the untested and taste the unknown.